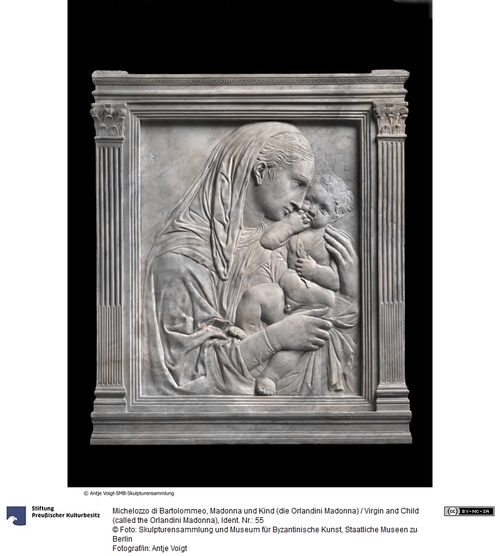

This marble relief is directly related to Donatello’s Pazzi Madonna; it was probably carved by his close collaborator during the 1420s and 1430s, Michelozzo. The refined treatment of details is particularly apparent in the hands of the Virgin. The frame shows a taste for Antique architecture that was quite precocious in Florentine art and may anticipate Michelozzo’s career as an architect.

Attributed to Michelozzo di Bartolomeo

Michelozzo di Bartolomeo Michelozzi

Florence 1396-1472

Virgin and Child (called the Orlandini Madonna)

ca. 1426

Provenance

Florence, palazzo Orlandini (until 1842); Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Altes Museum (1842-1904); Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum (1904-1939); Berlin, storage (1939-1945); Soviet Union, secret storage (1945/46-1958); East Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Bode-Museum (1958-1990); Berlin, Skulpturensammlung/Bode-Museum (1990-present).

Acquisition

Bought from the Orlandini family in Florence in 1842.

Restorations

1958; 1973; 2014.

Exhibitions

Das verschwundene Museum. Die Berliner Skulpturen- und Gemäldesammlungen 70 Jahre nach Kriegsende, Berlin, Bode-Museum, 19 March-27 September 2015.

Other versions

• Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Skulpturensammlung, Inv. SKS 1565. Painted stucco, 65.5 x 43.5 cm. Bought from Stefano Bardini in 1889. Now in the Bode-Museum, storage (mistakenly described as lost during WWII in Lothar Lambacher ed., Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Dokumentation der Verluste. Skulpturensammlung. Band VII. Skulpturen. Möbel, Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 2006, p. 159).

• Florence, Museo Horne. Painted stucco, 61 x 46.5 cm. Provenance: Siena, Via dei Maestri.

• Florence, Palazzo Vecchio, Charles Loeser Collection, Inv. MCF-LOE 1933-5. Terracotta, 78 x 66 cm.

• Formerly Art Market. Photo Kunsthistorisches Institut Florenz: n° 222692.

Bibliography

Tieck 1844

Frédéric Tieck, Musées Royaux. Notice des sculptures antiques, Berlin, Moeser and Kühn, 1844, p. 51 cat. 610: Donatello.

Kunstblatt, 1846

Kunstblatt, 1846, p. 245. (reference to be checked)

Bode 1884

Wilhelm Bode, “Die italienischen Skulpturen der Renaissance in den Königlichen Museen zu Berlin. III”, Jahrbuch der Königlich preußischen Kunstsammlungen, V, 1884, pp. 38-39: close circle of Donatello; pilasters similar to the ones of the Madonna in the Old Sacristy in San Lorenzo, Florence.

Bode 1886

Wilhelm Bode, “Neue Erwerbungen für die Abteilung der christlichen Plastik in den königlichen Museen”, Jahrbuch der Königlich preußischen Kunstsammlungen, VII, 1886, pp. 205-206: by a pupil of Donatello; the Orlandini provenance indicats that the work probably belonged to the Medici; weaker in quality than the Pazzi Madonna (Inv. SKS 51) which is certainly by Donatello.

Bode 1887

Wilhelm Bode, Italienische Bildhauer der Renaissance. Studien zur Geschichte der italienischen Plastik und Malerei auf Grund der Bildwerke und Gemälde in den Königl. Museen zu Berlin, Berlin, W. Speemann, 1887, pp. 9, 49-50.

Tschudi 1887

Hugo von Tschudi, Donatello e la critica moderna, Turin et al., Fratelli Bocca, 1887 (1st ed.: Rivista storica Italiana, IV, n° 2, 1887), p. 33: Donatello, ca. 1430; much inferior to the “Pazzi Madonna”.

Bode and Tschudi 1888

Wilhelm Bode and Hugo von Tschudi, Königliche Museen zu Berlin. Beschreibung der Bildwerke der Christlichen Epoche, Berlin, W. Spemann, 1888, p. 17 cat. 42: school of Donatello.

Bode 1894

Wilhelm Bode, Denkmäler der Renaissance-Sculptur Toscanas, Munich, F. Bruckmann, 1894, II, pl. 68: Donatello (caption of the plate).

Bode 1902

Wilhelm Bode, Florentiner Bildhauer der Renaissance, Berlin, Bruno Cassirer, 1902, pp. 99-100, 100 fig. 35: workshop of Donatello, ca. 1425 or slightly later.

Balcarres 1903

Lord Balcarres, Donatello, London and New York, Duckworth & Co. and Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903, pp. 181-182: after Donatello; another version is in the Bardini collection.

Meyer 1903

Alfred Gotthold Meyer, Donatello, Bielefeld and Leipzig, Delhagen and Klafing, 1903, pp. 60, 115: Donatello.

Schottmüller 1904

Frida Schottmüller, Donatello. Ein Beitrag zum Verständnis seiner künstlerischen Tat, Munich, F. Bruckmann, 1904, p. 36 note 4.

Schubring 1905

Paul Schubring, “Italienische Plastik”, Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, new series, XVI, 1905, p. 56.

Schubring 1907

Paul Schubring, Donatello. Des Meisters Werke in 277 Abbildungen, Stuttgart and Leipzig, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1907, pp. 173, 201-202: maybe by Buggiano; close to the relief on the altar of the sacristy of San Lorenzo, Florence.

Bode 1908

Wilhelm Bode, “Ein Blick in Donatellos Werkstatt”, Monatshefte für Kunstwissenschaft, I, n° 1-2, January-February 1908, p. 10: after an idea by Donatello.

Venturi 1908

Adolfo Venturi, Storia dell’arte italiana. VI. La scultura del Quattrocento, Milan, Ulrico Hoepli, 1908, p. 266 note 3: not Donatello.

Sirén 1909

Osvald Sirén, Florentinsk Renässansskultur och andra Konsthistoriska ämnen, Stockholm, Wahlström & Widstrand, 1909, p. 55 note 1: follower of Donatello.

Cruttwell 1911

Maud Cruttwell, Donatello, London, Methuen, 1911, pp. 134-135: “imitation of the ‘Pazzi Madonna’”.

Schottmüller 1913

Frida Schottmüller, Die italienischen und spanischen Bildwerke der Renaissance und des Barocks in Marmor, Ton, Holz und Stuck, Berlin, Georg Reimer, 1913, p. 16 cat. 31: young assistant of Donatello; comes from the Orlandini palace, so possibly inherited from the Medici; the capitals are in the style of Brunelleschi.

Bode 1921

Wilhelm Bode, Florentiner Bildhauer der Renaissance, Berlin, Bruno Cassirer, 1921, p. 96 fig. 51: workshop of Donatello.

Deri 1926

Max Deri, Das Bildwerk, Berlin, Deutsche Buch-Gemeinschaft, 1926, pp. 104-113: compared to the Pazzi Madonna, which is given to Donatello, whereas this one is attributed to his school.

Colasanti 1931

Arduino Colasanti, Donatello, Rome, Valori Plastici, n. d., pl. CCXL, French trans., Paris, Crès, 1931, p. 89, pl. CCXL: workshop of Donatello.

Schottmüller 1933

Frida Schottmüller, Die italienischen und spanischen Bildwerke der Renaissance und des Barock. Erster Band. Die Bildwerke in Stein, Holz, Ton und Wachs, Zweite Auflage, Berlin and Leipzig, Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1933, pp. 19-20: Andrea Guardi; the artist worked on the same bozzetto by Donatello as did Buggiano in his Virgin and Child in the Old Sacristy, San Lorenzo, Florence; p. 88: related to a Madonna and Child attributed to a Sienese artist ca. 1460 (Inv. SKS 1744).

Lensi 1934

Alfredo Lensi, La donazione Loeser in Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Comune di Firenze, 1934, pp. 27-29, pl. XII: Charles Loeser thought that his own version of the composition now in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence was by Donatello, and that the Inv. SKS 55 was a replica from the 19th century; the author thinks that the Berlin work is of lesser importance than the other, and is not worthy of Donatello himself. (reference to be checked)

Middeldorf 1933

Ulrich Middeldorf, review of Schottmüller 1933, Rivista d’arte, XX, 1938 now in: idem, Raccolta di scritti that is Collected Writings. I. 1924-1938, Florence, SPES, 1979-80, p. 379: too fine to be by Andrea Guardi (as stated by Schottmüller 1933); the frame is similar to the creations of Brunelleschi.

Buscaroli 1942

Rezio Buscaroli, L’arte di Donatello, Florence, Monsalvato, 1942, p. 149 cat. 96: by the same artist who made the Lombardi monument in Santa Croce, Florence.

Goldscheider 1947

L. Goldscheider, Donatello, Paris, Phaidon, 1947, p. 39 fig. 112: Andrea Guardi.

Verzeichnis 1953

“Verzeichnis der im Flakturm Friedrichshain verlorengangenen Bildwerke der Skulpturen-Abteilung”, Berliner Museen, new series, III, n° 1-2, 1953, p. 12: burnt in Berlin between 5 and 10 May 1945.

Janson 1957

H. W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1957, II, p. 44: “a much inferior marble variant of the Pazzi Madonna dating from the middle years of the Quattrocento”.

Grohn 1959

Hans Werner Grohn, “Report on the Return of Works of Art from the Soviet Union to Germany”, The Burlington Magazine, CI, n° 670, January 1959, p. 61: Andrea Guardi, “broken into three parts and the surface was disfigured by black burns at the time of the salvaging; the parts have been carefully and skillfully joined together again”. “It must be stressed that in no case were there any additions made in the process of restoration, but permanent losses of material were substituted by some neutral ingredient.”

Beck 1971

James H. Beck, “Masaccio’s Early Career as a Sculptor”, The Art Bulletin, LIII, n° 2, June 1971, pp. 178, 181 fig. 3: after Donatello, ca. 1450. The Christ with his fingers in his mouth is an invention of Donatello ca. 1420 that was copied here, and in Masaccio’s San Giovenale Triptych.

Fründt 1973

Edith Fründt, “Skulpturen-Sammlung”, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Forschungen und Berichte, 15 (Kunsthistorische und Volkskundliche Beiträge), 1973, p. 253: the work has just been restored.

Pope-Hennessy 1976, ed. 1980

John Pope-Hennessy, “The Madonna Reliefs of Donatello”, Apollo, CIII, n° 169, March 1976 now in: idem, The Study and Criticism of Italian Sculpture, New York and Princeton, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Princeton University Press, 1980, pp. 74-75, 103 note 7: unidentified imitator of Donatello, after the “Pazzi Madonna”.

Knuth 1982

Michael Knuth, Skulpturen der italienischen Frührenaissance, East Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 1982, pp. 34, 36: Andrea Guardi. (reference to be checked)

Sachs 1984

Hannelore Sachs, Donatello, East Berlin, Henschelverlag, 1984, chap. 6: Donatello; reproduced together with the Pazzi Madonna, then in West Berlin.

Gentilini 1985

Giancarlo Gentilini in Paola Barocchi et al. (eds.), Omaggio a Donatello. 1386-1986. Donatello e la storia del Museo, exh. cat. (Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, 19 December 1985-30 May 1986), Florence, SPES, 1985, p. 272: donatellesque; “modest creation”.

Neri Lusanna 1986

Enrica Neri Lusanna in eadem and Lucia Faedo (eds.), Il museo Bardini a Firenze. Volume secondo: le sculture, Milan, Electa, 1986, p. 249: repeats the comparison with Inv. SKS 57 made by Schottmüller 1933.

de Winter 1986

Patrick M. de Winter, “Recent Acquisitions of Italian Renaissance Decorative Arts. Part I: Incorporating Notes on the Sculptor Severo da Ravenna”, The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, LXXIII, 3, March 1986, p. 76: style of Donatello.

Joannides 1987

Paul Joannides, “Masaccio, Masolino and ‘Minor’ Sculpture”, Paragone. Arte, XXXVIII, new series, n° 5 (451), September 1987, pp. 5-6: not Donatello but workshop; mentions the painted copy by Giovanni Toscani; the pose of the Child is the source of the Fortnum Madonna by Luca della Robbia in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (see Inv. SKS 2303); Masaccio’s St Giovenale Triptych in Cascia di Reggello derives from the Orlandini Madonna; p. 21 note 18: influenced the pose of the Child in the Medici Madonna in the Old Sacristy, San Lorenzo, Florence.

Avery 1989

Charles Avery, “Donatello’s Madonnas Revisited”, in Donatello Studien, Munich, Brückmann, 1989, pp. 221-222, fig. 3: Andrea Guardi, after 1430; after a prototype by Donatello around 1429, which influenced also the Fortnum Madonna in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (dated 1429), a painting of a Virgin and Child by Giovanni Toscani (mid-1420s), and the Medici Madonna by Buggiano in the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo, Florence (1432).

Gentilini 1992

Giancarlo Gentilini, I della Robbia. La scultura invetriata nel Rinascimento, Florence, Cantini, 1992, I, p. 157 note 74: a less important artist than Donatello, possibly Andrea Guardi.

Jolly 1998

Anna Jolly, Madonnas by Donatello and his Circle, Frankfurt am Main et al., Peter Lang, 1998, pp. 107-108 cat. 19.1: Andrea Guardi at an early stage of his career, after Donatello, ca. mid-1420s; p. 186: compared to the Loeser Madonna in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, said to have been attributed to Michelozzo by Lensi 1934 but see Lensi 1934.

Katalog der Originalabgüsse 2000

Katalog der Originalabgüsse. Heft 6. Christliche Epochen. Spätantike. Byzanz. Italien. Freiplastik. Reliefs. Bronzestatuetten, Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2000, cat. 2632: attributed to Andrea Guardi.

Sorce 2003

Francesco Sorce, “Guardi, Andrea”, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, 60, Rome, Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 2003, pp. 286-287: follows the attribution to Andrea Guardi recently made by Avery, and the dating before 1432.

Boskovits 2007

Miklós Boskovits, “Wilhelm von Bode als Kunstkenner”, in Stefan Weppelmann (ed.), Zeremoniell und Raum in der frühen italienischen Malerei, Petersberg, Michael Imhof Verlag, 2007, p. 19: follower of Donatello.

Warren 2014

Jeremy Warren, Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture. A Catalogue of the Collection in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Volume 2. Sculptures in Stone, Clay, Ivory, Bone and Wood, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum Publications, 2014, p. 387: after 1430; Christ sucking his fingers derives from Masaccio and influenced Buggiano in the Medici Madonna (1432) in the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo, Florence.

Chapuis and Kemperdick 2015

Julien Chapuis and Stephan Kemperdick (eds.), The Lost Museum. The Berlin Painting and Sculpture Collections 70 Years after Wold War II, exh. cat. (Berlin, Bode-Museum, 19 March-27 September 2015), Berlin and Petersberg, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin and Michael Imhof Verlag, 2015, pp. 122-123: attributed to Michelozzo; on the damages of WWII on the relief, and its restoration in 2014.

Rowley 2015

Neville Rowley, “Wie man ein Denkmal wird. Wilhelm Bode und die Berliner Museen 1883/84”, in Nikolaus Bernau, Hans-Dieter Nägelke and Bénédicte Savoy (eds.), Museumsvisionen. Der Wettbewerb zur Erweiterung der Berliner Museumsinsel 1883/84, exh. cat. (Berlin, Bauakademie, 16 September–11 October 2015), Kiel, Ludwig, 2015, p. 80: attributed to Michelozzo.

Comment

The Virgin holds the naked Christ against her face and body; Jesus is biting his right hand, while holding with the left one a coral branch attached to his neck. He looks at the viewer, while his left foot rests on the edge of the relief frame. The ground around the figures is neutral, while the frame, made of the same marble block, is an Antique-style niche with fluted pilasters and Corinthian capitals.

This relief was acquired for the Berlin Museums by Gustav Waagen in Florence in 1842, as a work by Donatello. It was said to come from the Orlandini palace in Florence, and was by then frequently named the Orlandini Madonna. In 1884, Wilhelm Bode published an engraving of the work, describing it as from the very close circle of Donatello, the pilasters of the frame reminding him of the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo in Florence, built by Filippo Brunelleschi and partly decorated by Donatello (Bode 1884). In 1886, Bode changed his mind: the work was described as much weaker than a genuine production of Donatello, the Pazzi Madonna (Inv. SKS 51), that Bode had just acquired for the Berlin Museums (Bode 1886; see Rowley, 2015).

A few artists have been proposed as authors of the relief. Schubring 1907 had thought of Buggiano, the adoptive son of Filippo Brunelleschi and author of a Virgin and Child in the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo, Florence (often called the Medici Madonna), dated 1432, as the composition and the gesture of the Christ biting his hand are close to our work; while Schottmüller 1933 attributed the Orlandini Madonna to a follower of Donatello in Pisa, Andrea Guardi (Schottmüller 1933). Both scholars clearly considered the relief a minor work, and their opinions should be seen in conjunction with each other, as Frida Schottmüller refused to acknowledge the body of works reunited by Schubring under the name of Andrea Guardi (for this point, see the entry about a Virgin and Child after Guardi, Inv. SKS 2012). Even if Schottmüller’s attribution was immediately refuted by Middeldorf 1938, who thought the relief too fine to be by Guardi and its frame could have been conceinved by Brunelleschi, the name of Andrea Guardi remained connected to the relief for decades (see Goldscheider 1947; Knuth 1982; Avery 1989; Gentilini 1992; Sorce 2003).

After WWII, the state of the sculpture did not help any reconsideration: damaged in the Flakbunker Friedrichshain fires in May 1945, and secretly transferred to Moscow in 1946, it came back in a restored state that showed the damages of fire (the transfer to the Soviet Union is documented in Konstantin Akinscha, Grigori Koslow and Clemens Toussaint, Operation Beutekunst. Die Verlagerung deutscher Kulturgüter in die Sowjetunion nach 1945, Nuremberg, Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, 1995, p. 29: in July 1946, the described “half-length figure of the Virgin and Child by Donatello. Broken into many pieces. The marble is burned at the surface. The right elbow of the Virgin is covered with soot (Ein Relief rechteckiger Form aus Marmor. Halbfigur der Jungfrau mit Kind von Donatello. In viele Stücke zerbrochen. Der Marmor ist an der Oberfläche verbrannt. Der rechte Ellenbogen der Jungfrau ist mit Ruß bedeckt)” can only be the Orlandini Madonna, which is furthermore matched by the photographs of the work taken in the Soviet Union before its restoration.

In 2014, a restoration conducted by Paul Hofmann and Bodo Buczynski allowed the relief to be seen in a new light. Many details of the work appeared to be of the highest quality when seen at close range. This is especially the case of the fingers of the figures: the right hand of the Virgin (with delicately carved wrinkles in the joints) holds the Child’s leg with great spatial effect, the upper part of the fingers seemingly sinking into the relief, while the index finger of the left hand is in extremely shallow relief; the Christ is forcefully holdling onto a coral (an apotropaic organism often associated with healing, visible for instance in Piero della Francesca’s Montefeltro Altarpiece in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan) and biting his right hand, in a naturalistic gesture. Other details, such as the Virgin’s hair, her diadem, or the draperies, call to mind Donatello’s work.

The general conception of the relief is, however, somewhat different from the ascertained works by Donatello. The space around the figures is not worked as in Donatellesque reliefs (such as the Pazzi Madonna Inv. SKS 51 with its perspective niche, but also, more evidently, the Assumption of the Virgin in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where no flat surface is left). Furthermore, the Virgin’s anatomy is not entirely convincing, especially the junction of the breast with the rest of the bust. For these reasons, one can assume that the Orlandini Madonna is by an artist very gifted and close to Donatello. This artist cannot be Andrea Guardi, whose style is too characteristic (and too weak) for such a work (in Spring 2015, this was also the opinion of Gabriele Donati, the author of a forthcoming monograph on Guardi). The closest parallel to the Orlandini Madonna appears to be the virtues at the base of the tomb of Cardinal Rinaldo Brancacci in Sant’Angelo a Nilo, Naples, which have almost unanimously been attributed to Donatello’s collaborator at the time, Michelozzo di Bartolomeo. The Orlandini Madonna is then very likely by Michelozzo, even if the authorship of another pupil of Donatello’s in this period (such as Pagno di Lapo Portinari, also documented for the Neapolitan tomb) cannot be absolutely ruled out.

As the Brancacci Tomb in Naples dates to 1426-28, these years are the likely dating of our relief, which was certainly made before the end of the decade, as a painting by Giovanni Toscani (died 1430) directly echoes the work (see Joannides 1987). The iconographical detail of Christ putting his fingers in his mouth is visible is Masaccio’s Pisa Altarpiece, also made in Pisa in 1426 – it is tempting to think that Michelozzo took this motif from Masaccio in Pisa (the painter already used it in his St Giovenale Triptych in Cascia di Reggello, dated 1422). A few derivations in stucco from the Orlandini Madonna exist (notably in Berlin, see Inv. SKS 1565); the one in the Museo Horne comes from Siena, like a more indirect and later version once in the Berlin Museums and lost during WWII (Inv. SKS 1744). To have further indication about the original provenance of the relief, it is necessary to investigate on the Orlandini provenance in Florence.

Neville Rowley (15 February 2016)

de